How should the NSWBA address environmental degradation?

The editorial of the NSWBA Newsletter, Summer 2015, posed the question as to how the Atlassers should address the problem of environmental degradation.

As a group, the most obvious approach to environmental degradation is for the Atlassers to become ‘politically’ active but the question of whether NSWBA should, instead, stand on the sideline as a respected fact-gathering organisation without a political agenda is, of course, open to serious debate.

Regardless, for some individuals the potential for the environmental degradation of a particular site can sometimes become so great that, personally, they feel the urge to lash out, to take matters into their own hands, to do something, anything. But what?

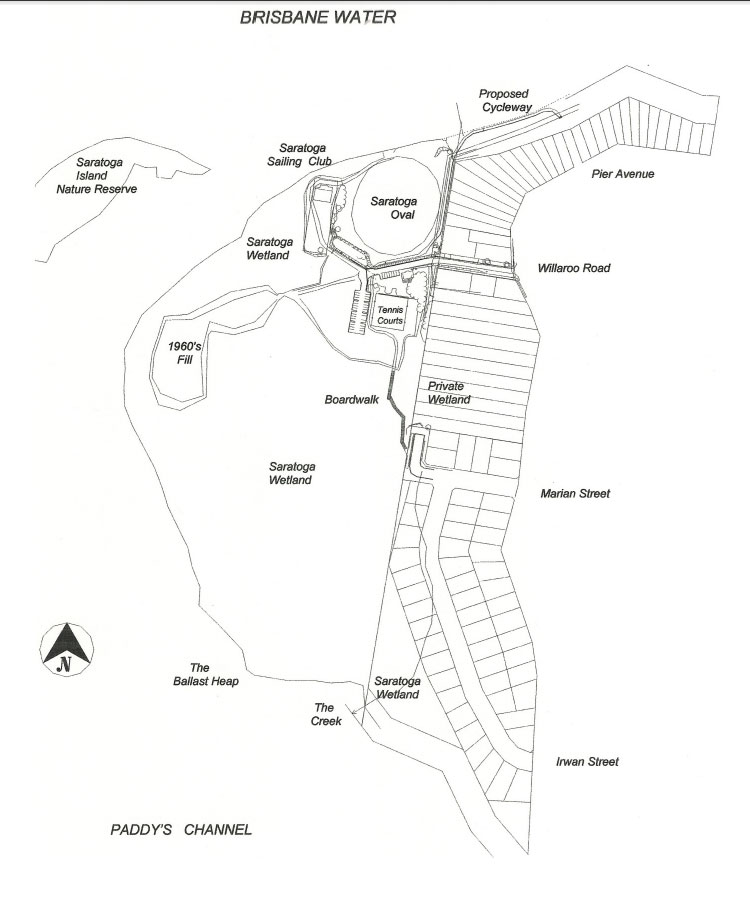

To assist Atlassers who do wish to address environmental degradation, I offer below an account of my personal observations and experiences over the past forty years or so in the struggle to preserve just one small parcel of Crown Land, Reserve R64760 on the western tip of the Saratoga peninsula on the NSW Central Coast. A map of the reserve is attached but a more detailed view can be found on Google maps etc by entering the name of the reserve’s vehicular access, Willaroo Road, Saratoga.

Background

Reserve R64760 is an area of state-owned Crown Land that was gazetted as a reserve for public recreation in 1934. The reserve has an area of approximately 14 hectares and extends some 650 metres north-south and 300 metres east-west, bordered to the east by residential allotments and elsewhere by Brisbane Water, the northern arm of Broken Bay. At the time of its gazettal, Reserve R64760 was entirely an estuarine wetland with the shoreline predominantly covered with mangroves, backed by open expanses of saltmarsh and, on the marginally higher areas, small pockets of swamp-oak forest. Offshore, relatively extensive mudflats are exposed at low tide while to the north-west is a small sand island, the result of dredging in the early 1900s to create a navigable channel for boats ferrying residents and holiday-makers between Saratoga and Woy Woy where supplies could be bought and a railway station provides a link to Sydney, or Newcastle.

In the 1930s a general assessment of the worth of Reserve R64760 would have been that it was an unproductive wasteland which, most likely, had been degraded to some extent by the occasional grazing of cattle since the mid-1800s and the gathering of shells in those days for the production of lime.

After the land was set aside for public recreation in 1934 the local council was assigned a ‘caretaker’ role in the administration of the reserve and sometime later the north-east corner was cleared and filled to create an undersized, low-lying oval, probably with the full support of the local community. Saratoga Oval, as it came to be known, remains mostly unaltered to the present day.

1960s

The 1960s brought huge changes to the Brisbane Water area. The introduction of electric train services between Sydney and Gosford and the gradual expansion of the town water supply to the outer localities of the shire resulted in an influx of former holiday-makers as permanent residents who converted their ‘week-enders’ into more substantial homes and either retired or were prepared to commute daily by train to their workplaces in Sydney.

Prior to the 1960s, in waterfront villages such as Saratoga, holiday-makers had visited primarily to enjoy the waterways, participating in activities such as fishing and crabbing. As permanent residents, though, those very same people then also wanted to enjoy mainstream sports such as cricket and football but while there were numerous foreshore reserves and public wharves in the district to cater for boating activities, little or no provision had been made in the past for other forms of recreation. Filling the wetlands to develop sporting facilities was seen as a logical option.

Development regulations in the 1960s were nothing like today’s and the local council, under unprecedented pressure, proceeded without question to fill several wetlands around the Brisbane Water foreshores to develop sporting fields, typically by using those wetlands as rubbish tips for a few years and then covering them with a layer of soil to provide a playing surface. Little or no thought was given to the impact of such practices on the environment but one seemingly unrelated consequence was the gradual but noticeable decline of marine life.

For Reserve R64760 at Saratoga the council’s plan was to first dredge the sand island that lies to the north-west of the reserve and pump the spoil directly into the wetland. The intention was to remove the island completely and fill the entire reserve for football fields, bowling greens and basketball courts, very similar to a major sporting complex that has been developed at Adcock Park, West Gosford, another site that was previously an extensive estuarine wetland, then rubbish tip.

The council’s attempt to develop Reserve R64760 at Saratoga in the 1960s was, however, short-lived. Paddys Channel, historically the most popular fishing ground in Brisbane Water, adjoins Reserve R64760 and it seems there may have been some local fishermen at that time who understood the severity of the environmental damage that was about to be inflicted. From whatever cause, the council’s dredge sank in Paddys Channel soon after pumping began, the filling of the wetland ceased immediately and the entire project came to an abrupt halt.

DIRECT ACTION can be very successful, but probably not recommended in this day and age of increased surveillance.

1970s

The urge for humans to modify their environment to suit their own ‘needs’ is unrelenting.

Encouraged by a local sporting organisation that was formed during the 1970s specifically to pursue the development of Reserve R64760, the council next proposed a lesser development of the reserve and, as a concession to the growing concern for the environment, modified its former plans to allow the southern half of the reserve to be rezoned for the protection of flora and fauna.

My personal interest in the development of the reserve began in 1975 while involved in a survey of the wetland for the design of two tennis courts. A year later my wife, Jann, and I purchased a property adjoining the reserve. Each of us had grown up across the bay at Koolewong with Brisbane Water as our playground and moving to a new home at Saratoga, within a stone’s throw of the waterfront, seemed a natural progression. Before we relocated we were already aware that there were long-term plans to fill the northern half of the Saratoga wetland for sporting fields and we eagerly awaited that development. Not for one second did we imagine that, instead, opposing the environmental degradation of the reserve would consume so much of our lives in the future.

How could we have been so naïve?

I can still remember clearly how disappointed I had been to watch, as a teenager in the 1960s, the very first flow of silt I had ever seen running into Brisbane Water after heavy rain, the result of a subdivision under construction on the Koolewong hillside. I can also remember with disgust the amount of raw sewage that some neighbours regularly pumped into the stormwater drains or directly into Brisbane Water before the implementation of the council’s sewerage scheme. Undoubtedly as a direct consequence of increasing pollution, by the time I was thirty years of age and about to move to Saratoga, the pods of dolphins that regularly came into the bay when we were kids were a thing of the past. Gone too were the schools of surface fish accompanied by flocks of sea-birds wheeling overhead, and the runs of mullet that were so dense that it was impossible to see past them to the depths below. Yet, in my ignorance, like many others I still thought nothing of making use of the council’s rubbish tips within former foreshore wetlands at Woy Woy and West Gosford, both of which were destined to become sporting fields. Making good use of those ‘wastelands’ seemed like a worthwhile idea to me at the time.

The turning point that changed our perspective and convinced us that, as a community, we were heading down a path of destruction was nothing more than the wail of a pair of Bush Stone-curlews outside our lounge room window one night soon after moving into our new home. No-one who has ever experienced the call of a Bush Stone-curlew at such close quarters in the dark of night could ever forget that sound. Not knowing what was causing those eerie calls sent shivers through us but we did manage to sneak a look at the culprits before they moved off. A few days later Jann purchased a bird book as a Christmas present for me and our interest in bird-watching began. To this day I cannot believe how ignorant I had previously been of the natural world around us, even though practically all of my recreational pursuits to that time had centred on Brisbane Water, whether fishing, crabbing, sailing or just simply swimming.

Armed with my new bird book, within a couple of years of moving to Saratoga we had identified almost one hundred species of birds within the reserve and on the surrounding mudflats. Although the actual number of birds was small, the variety of species was more than ten percent of all the bird species within Australia and more than are found in some National Parks! Some of those birds are permanent residents of the area, a few are rare, some are endangered, others are obviously only occasional visitors, while several migratory species regularly fly in from as far as Siberia to spend the summer months on our foreshores. We were astounded but, now to our dismay, throughout the late 1970s the council began to randomly truck fill into the northern part of the wetland while to the south an area of privately-owned wetland adjoining the reserve was being cleared of mangroves and filled for a fifty-lot housing estate.

EDUCATION of a community in the worth of their local natural environment is an essential step in the process of addressing the degradation of a particular site.

1980s

By 1980 parts of the remaining wetland within Reserve R64760 had been cleared of mangroves and filled, allowing two tennis courts and a sailing club to be constructed to the council’s plan, but the reserve was still without a formal parking area, paving or drainage. In anticipation of further filling of the northern half of the reserve, the council also declared part of the wetland to be an off-leash dog exercise area. To us, immediate action was needed to protect the Bush Stone-curlews and other birdlife that just a few years earlier we didn’t even know existed.

But what action could we take? We were faced with exactly the same dilemma for which Ian Bailey, the editor of the NSWBA Newsletter, has recently sought answers in his editorial.

Fortunately, during the mid-1980s state environmental regulations began to come into effect, placing restrictions on development. For any future work within Reserve R64760 the council would be required to conform to those regulations and, importantly, was obliged to advertise any proposed development and accept submissions for and against. Although the unfilled portion of the reserve had, by then, been designated as wetland under state environmental planning policies, the council was reluctantly permitted to pursue its pre-existing development proposal.

My initial response was to begin weekly records of our observations of the various bird species that inhabited the reserve in the hope that somehow, sometime, the data could be used to help prevent further degradation of the site.

In due course I have come to realise that SITE-SPECIFIC DATA COLLECTION is crucial in the struggle against environmental degradation.

1990

In 1990, for the very first time, the local council formally advertised its proposal to complete the development of the northern half of Reserve R64760 and called for submissions for and against. By then, besides two football fields, the development application included a spectator mound and a regional boat ramp with sixty or more parking spaces for cars and trailers. But, at last, residents and others had the opportunity to legitimately oppose the proposal.

There were objections to the council’s proposal to fill the Saratoga wetland from departments within the state government and from conservation groups such as the Australian Conservation Foundation. Jann and I also played our small part in opposing the council’s development application. To help combat the proposal, from 1986 onward I had kept weekly records of the bird species and their numbers observed by us within the vicinity of the reserve and the surrounding mudflats and, in my very first attempt to influence a politician, had forwarded a lengthy hand-written submission to some of the councillors directly. Meanwhile, Jann had bravely door-knocked Saratoga to collect more than four hundred signatures on a petition objecting to the filling of the wetland. From the mayor at that time, a young man in his early twenties and a potential Liberal politician, I received a reply telling me that he agreed with my assessment of the environmental issues I had raised. Like Jann and me, he had apparently grown up alongside Brisbane Water and was obviously concerned about the environmental degradation that had already been brought about by inappropriate development. Finally, when it came to the vote the council was deadlocked and the mayor had the casting vote, rejecting the council’s proposal. In lieu of the proposed development, the council voted to ‘tidy up’ the already-filled north-eastern areas of the reserve instead. Everyone was stunned, including us.

Despite the fact that the council at that time was considered to be heavily biased in favour of development and despite the strong support of the local progress association and the four hundred or so members of the sporting organisation formed to encourage the development of the reserve, the council had actually rejected its own development application, to everyone’s surprise.

Like it or not, THE MANAGEMENT OF OUR ENVIRONMENT IS ULTIMATELY DETERMINED BY POLITICIANS and so the primary aim in addressing environmental degradation should be to assist and influence the politicians in their decision-making. Unfortunately, though, politics is a scheming game of numbers that is often swayed by factors that have little to do with logic, or facts.

SUBMISSIONS are routinely ignored or neutralised to achieve a predetermined outcome.

PETITIONS can also be ignored and often are.

REPORTS to politicians by staff or consultants to aid in the decision-making process can be inaccurate or deliberately biased to achieve a particular outcome. As a clear-cut example, the petition of more than four hundred signatures, mentioned above, was, in fact, reported to the councillors as a petition of only forty signatures. Whether the incorrect number of petitioners on record was a genuine mistake or a deliberate ploy to downplay the community’s opposition to council’s project is open to question.

VIGILANCE in overseeing the whole decision-making process is essential.

1995-2004

During the mid-1990s, quite oddly, I found myself elected president of the very same sporting organisation that had originally been formed to pursue the development of Reserve R64760, the very same organisation which my wife and I had previously so openly opposed some five years earlier. By then, though, the club had disintegrated after the rejection of the council’s development application in 1990 and just a handful of members remained to manage the tennis courts within the reserve.

In 1995, as a representative of the sporting organisation, I was approached by a councillor, a former mayor who lived locally, questioning how best to spend a small amount of money that was available for use within Reserve R64760. My immediate response was the necessity to develop a plan of management for the entire reserve that was practical and likely to be acceptable to the whole community. Within a week I had sketched preliminary plans for the reserve’s ‘development’ plus another plan for a proposal to build a cycleway/boardwalk link from Saratoga to nearby Kincumber via our local wetlands and foreshores. Everyone was rapt. A few years of politics followed before the council came onboard and then about three more years of extensive community consultation until the Saratoga Recreation Area and Wetland Plan of Management was finally adopted in 2004. In the meantime new amenities and a carpark had been constructed on the already-filled parts of Reserve R64760, the cycleway link to Kincumber was in the pipeline and a Central Coast Friends of the Bush Stone-curlew plus a Bushcare group to work in the Saratoga wetland had been formed. At that time the reserve was unique in that it was the only recreational reserve of its kind within the Gosford local government area to have its own plan of management. Independently, the year after the plan of management was adopted, the adjacent sand island was formally placed in the hands of the NSW Department of Environment and Conservation (NPWS) and is now known as Saratoga Island Nature Reserve.

From my perspective in 2004, the struggle to preserve Reserve R64760 had been successful and the future of the wetland and its flora and fauna was assured.

The proposed foreshore cycleway link between Saratoga and Kincumber would have more than one function. First and foremost the boardwalks through the wetlands would allow much-needed pedestrian access to otherwise isolated parts of the district. Carefully located, the boardwalks would also form a physical barrier to the motorcycles and other vehicles that often entered the wetlands from private property and finally, something as simple as an enjoyable walk along the boardwalks could alter the community’s appreciation of the wetlands for the better. I felt that the construction of a carefully planned cycleway link was not necessarily to the detriment of the wetlands but that there could be benefits as well, which has since proven to be the case. Previous generations would have and often did treat those very same wetlands as wasteland and, looking back, it had been as recently as 1990 that the council had itself lodged a development application to fill much of the Saratoga wetland for sporting fields. But, in a complete turnaround, since the construction of the cycleway link local residents have actually taken to the streets to demonstrate against the sale of a privately owned local wetland for possible development as a housing estate, an action that would have been considered irrational by one and all in the not too distant past.

After an ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT, a PLAN OF MANAGEMENT is an essential next step in the land management process to prevent willy-nilly development and to minimise the degradation of the environment.

NEW PROJECTS have a particular appeal to politicians and the public alike. The possibility of constructing, say, a boardwalk can have a major impact on how politicians and the general public perceive a particular parcel of land which, in turn, can also reduce the potential for environmental degradation. Politicians and public servants prefer to have such projects fully researched and planned when presented to them so that a project can proceed quickly and without fuss.

FUNDING, perhaps for an entire site, often depends on the perceived popularity of the project.

SPORTING ORGANISATIONS seem to have undue influence in the world of politics. Governments at all levels have happily combined in the past to finance, on the Central Coast, a multi-million dollar stadium but generally ‘lack the resources’ to finance even the smallest of environmental projects. Linking the preservation of the environment to recreational pursuits can be beneficial.

The presence of an ENDANGERED OR THREATENED SPECIES on-site is invaluable. For Reserve R64760 the fact that Bush Stone-curlews had inhabited the reserve throughout living memory has been a distinct bonus. The eventual development of the recreational area of the reserve was heavily influenced by the presence of Bush Stone-curlews, particularly the fact that, at night, the open grassed areas constitute a major portion of the birds’ foraging habitat.

Equally invaluable has been THE ASSISTANCE OF ENVIRONMENTAL PROFESSIONALS who collaborated to form the Central Coast Friends of the Bush Stone-curlew, a small group which includes a respected, well-known ornithologist who was once the local regional manager of NPWS and another authority on Bush Stone-curlews, the author of the Recovery Plan for the Bush Stone-curlew, adopted in 2006 by the NSW government.

The formation of a wetland BUSHCARE group helped to bring a handful of like-minded local people together and drew the council’s attention to the invasion of the wetland by exotic plants. Although truck loads of weeds such as Asparagus Fern were removed from the fringes of the wetland by the Bushcare group, the group was eventually disbanded due to lack of support by the community. Operating for about a five year period, the Bushcare group’s long-term impact on the eradication of the exotic weeds was disappointingly minimal and short-lived compared with subsequent work done by professional teams using chemicals. In retrospect, Bushcare within the wetland may have been more successful if confined to a ‘tidy up’ role with a much lighter workload. Those initial years could have been better spent carefully listing, photographing and mapping the flora and fauna within the reserve for future reference, in much the same way that the NSWBA functions, and then move on to the monitoring of the flora and fauna within the reserve and publicising the results, particularly within the local community.

2010

The plan of management for Reserve R64760 had been some four or five years in the actual making, first involving an environmental assessment followed by a masterplan and ultimately the plan of management itself, the whole process including three years of intensive community consultation. A draft plan of management for Reserve R64760 was adopted by the council and the state government in 2003 and the final document in 2004. Importantly, as part of the recognition of the environmental worth of the grassed recreation area, particularly as Bush Stone-curlew foraging habitat, the draft plan of management required that dogs be kept on-leash within the recreation area and, obviously, prohibited from the wetland. Incredibly, within just a few weeks of adopting the draft plan of

management, the very same councillors, faced with a vocal dog-owner lobby in the public gallery, chose to ignore recommendations from council’s staff and (illegally) declared Saratoga Oval to be a dog off-leash exercise area. Ignoring complaints, the council refused to suspend the off-leash dog exercise area until 2010, some six years after adopting the final plan of management and only then after a hint of legal action, more investigations by consultants and finally an admission of the fact that the off-leash area was in conflict with the plan of management for the reserve.

Dogs, particularly off-leash and roaming, are a major threat to the survival of ground-dwelling bird species such as the endangered Bush Stone-curlew that inhabit parts of the Brisbane Water foreshore. However, Gosford City Council, over many years, has consistently shown it lacks the will and the backbone to deal with the large and very vocal dog-owner lobby on the Central Coast. The obvious question, therefore, is what factors caused the council to eventually revoke the off-leash dog exercise area on Saratoga Oval in 2010?

In short, the contents of a NSWBA newsletter!

In 2009, a NSWBA newsletter told of how birdwatchers on the NSW north coast had instigated a court case against their local council. In February of that year the NSW Land & Environment Court delivered sentence against both Port Macquarie – Hastings Council and, importantly, its Director of Infrastructure. Port Macquarie – Hastings Council was ordered to pay fines and costs totalling $274,000 for breaches of the National Parks and Wildlife Act and Fisheries Management Act. The director was ordered to personally pay $224,500 for offences against the National Parks and Wildlife Act. The court found that the director had knowingly failed to comply with the requirements for environmental assessment for works carried out on environmentally sensitive land, with the effect that damage was caused to the habitat of threatened species including the Grass Owl and its prey, the Eastern Chestnut Mouse. Without approval, the director had instructed access roads to be constructed within wetland which was an area identified as having acid sulphate soils and the construction of the roads had resulted in the disturbance of the habitats of the two threatened species. The judgement highlighted the importance of compliance with environmental and planning legislative requirements, particularly those relating to the preservation and protection of certain species under the National Parks and Wildlife Act and the Threatened Species Conservation Act 1995 (NSW).

With knowledge of the NSW Land & Environment Court decision I immediately wrote to the mayor of Gosford City Council and his fellow councillors and, quoting that decision, politely requested that Council revoke all of its off-leash dog exercise areas within known Bush Stone-curlew habitat on the Brisbane Water foreshores. Within three working days, at the very beginning of the next council meeting, the off-leash areas in question were suspended as a matter of urgency! The threat of heavy personal fines and possible prison sentences can have an amazing effect on a person’s decision-making.

The LAW is a powerful ally. Any opportunity for pursuing legal action to prevent environmental degradation should always be investigated (but is extremely difficult to fund).

2013

Before the first draft plan of development of Reserve R64760 was presented to the public, in 1998 the plan was first circulated to stake-holders for comment. On that very first draft, council had included floodlighting of Saratoga Oval and the future carpark. Immediately, the floodlighting was objected to by NPWS because of the presence on the oval at night of Bush Stone-curlews. The EIS for the proposed development later recommended that all lighting within the reserve be turned off by 8:30pm. Consequently, the first draft plan of development was amended accordingly and subsequent plans presented for public discussion did not include floodlighting and the matter was never publicly debated during the community consultation process. The word ‘floodlight’ is nowhere to be found in the final plan of management, adopted in 2004, nor do any of the plans within that document give any indication of future floodlighting towers even though the intended locations of much smaller items such as signage are clearly shown.

Incredibly, in 2011 Gosford City Council included with its rate notices an announcement that $195,000 had been allocated for the upgrade of the (non-existent) floodlighting of Saratoga Oval and that an additional grant of almost $50,000 had been allocated by the state government.

According to a council pamphlet, the (non-existent) floodlights were planned to be ‘upgraded’ in the next financial year. That decision was a handshake deal, apparently, brought on by the persistent requests of a local junior football club. Immediately I wrote to the council, reminding them of the existence of a plan of management for the reserve and of the fact that Bush Stone-curlews are classified as endangered and that Saratoga Oval is formally recognised as Bush Stone-curlew foraging habitat. The first reaction of the council was stunned silence, presumably to check whether a plan of management really did exist, followed some time later by a reply from a senior member of council staff that simply explained that ‘times change’. Later still came the explanation that floodlighting was actually permitted by the plan of management (it just took some imagination to interpret outdoor lighting of an amenities block to actually mean that a whole oval could be flooded with light from three towers at a cost of almost a quarter-million dollars). So important had the floodlighting of our undersized, low-lying, little-used oval become that as soon as criticism emerged, the mayor, the local state member (himself a former mayor) and the NSW Minister for Sport (a former NRL referee) collaborated to make a joint announcement on-site to the local media and regional television! Until then, some of the other councillors had no knowledge whatsoever of the intention to install floodlighting on Saratoga Oval.

Despite the fact that the council reasoned that floodlighting of Saratoga Oval was permissible under the plan of management, a consultant was later commissioned to determine the potential impact on the Bush Stone-curlews. As a matter of interest, during the 2010 off-leash dog episode, another ‘independent’ consultant commissioned by the council was able to report that Bush Stone-curlews could not possibly exist within the reserve due to the incompatible habitat, ignoring more than twenty years of records in the council’s possession. To resolve the floodlighting issue, the council’s consultant reported that the impact on the Bush Stone-curlews would be minimal, submissions for and against were eventually called for and ignored and, finally, the matter went before the whole council for approval. Council’s argument was that it was in the difficult predicament of having to strike a ‘balance’ between the needs of the community and protecting the environment. The floodlights were installed in 2014 and supposedly can only be used for two nights per week until 8:30pm, effectively restricting their use to football training during the winter football season.

The argument often used by politicians of having to strike A BALANCE BETWEEN THE NEEDS OF A COMMUNITY AND THE PROTECTION OF THE ENVIRONMENT is no more than a scam to fool a gullible audience. Years ago, when my kids were little, I could sometimes trick them into eating their vegetables by telling them they only had to nibble away at half of what was left on their plate. Even as little kids they soon caught on that eventually the plate would be completely empty.

NEVER TRUST A POLITICIAN, with apologies to the handful that might actually be honest and prepared to always do things ‘by the book’.

NEVER TRUST A PUBLIC SERVANT to either do their job satisfactorily or to contradict their masters.

I would also add, NEVER TRUST A JOURNALIST. Journalists, in my experience, seem much more interested in a conflict that can give them a catchy headline or fill the front page of their newspaper than in pursuing the facts of a matter.

The struggle to prevent floodlighting from being installed on Saratoga Oval to the detriment of the endangered Bush Stone-curlews and, previously, the campaign to have illegal dog off-leash exercise areas revoked from the oval and some other foreshore locations of known Bush Stone-curlew habitat, sometimes involved writing letters to the editors of the local press to gain public support against the council’s actions. As expected, in each instance, instead of logical argument, the letters generated an outburst of personal abuse hurled at me from football club supporters and dog-owners respectively. One football club supporter, who I have never met, even wrote to the local newspaper claiming nothing else other than that I do not like lights, dogs, activities in my area, sport, kids sport and children in general. The personal abuse overflowed into social media and insults and outright denials of the existence of Bush Stone-curlews on the Central Coast became the order of the day for many. The local newspapers were never, at any time, interested in investigating or publishing the facts of either of those two episodes that were such an obvious threat to the local environment and by allowing the outlandish views of some readers to be published actually contributed to the environmental degradation that later occurred. But, at least everyone in the district had been exposed to the presence of the local Bush Stone-curlews and their plight.

NO AMOUNT OF LOGIC OR EDUCATION CAN SWAY THE OPINION OR BEHAVIOUR OF BLOCKHEADS and be warned, blockheads are often disguised as respectable people who claim to care for the environment.

The Present

For more than fifty years a battle of sorts has been waged between a handful of local residents and the community, represented by the local council, to preserve Reserve R64760 from environmental degradation.

Today, in 2015, the community is represented by a council biased, more than ever, towards development and whose motto is simply ‘open for business’. That business, with the support of the state government, includes the aim of turning over parts of the public reserves on the Brisbane Water foreshore to privately-owned high-rise residential and commercial development. Admittedly, the current proposals are for the development of the already-filled, sterile land on the Gosford waterfront and one could assume that Reserve R64760 at Saratoga now has adequate protection from such schemes, but nothing is sacred to those in power who are motivated solely by economics.

Reserve R64760, despite its history, is under pressure regardless, mainly from a rising population that seems to be increasingly detached from the natural world and a council that, despite the projected public image, in practice places protection of the natural environment at the very bottom of its priorities.

Besides human activity, dogs are responsible for diminishing much of the bird life within Reserve R64760 as they are in other parts of the Central Coast, with little or no resistance from the council. Signs within Reserve R64760 to keep dogs on-leash at all times are constantly ignored by dog-owners and there is often a constant stream of dogs being run off-leash, not only within the recreation area but also within the Saratoga Island Nature Reserve which is easily accessed through the wetland at low tide. In the recent past a visit to the island could lead to the observation of several species of migratory waders in summer and other waders all year round. Today, instead, the most likely observation is a dog being run off-leash, or fresh dog tracks on the sand and not a bird in sight.

The Bush Stone-curlews, in particular, have been under pressure from human activity and roaming dogs for years within Reserve R64760, forcing the birds to roost by day in the heart of the tidal wetland instead of their preferred location, under trees on the fringe of the open grassed areas. Domestic cats, roaming the reserve at night from nearby residences, add to the birds’ problems. Sadly, in recent weeks the Bush Stone-curlews seem to have abandoned the reserve as their permanent habitat. Although Bush Stone-curlews can fly long distances, they are ground-dwelling birds that forage, roost and nest on the ground, usually at the same location for all of their lives, which can be upwards of thirty years. An area the size of Reserve R64760 is capable of supporting only one pair of Bush Stone-curlews and that pair will typically stay together and vigorously defend their habitat from others. In late spring, 2015, the Bush Stone-curlews of Reserve R64760 nested, only to have their nest destroyed, possibly by an animal but more likely, I suspect, by human interference, leading to what now appears to be an abandonment of the reserve as the permanent habitat of the birds for the first time since my wife and I have been observing them. For us, the continued presence of the Bush Stone-curlews has been the ‘litmus test’ of the worth of our efforts to protect our local environment. Now, it seems that after four decades, our struggle to prevent the degradation of the Bush Stone-curlew habitat within Reserve R64760 has ultimately failed, a judgement made by the birds themselves.

Despite the recent loss of the Bush Stone-curlews, Reserve R64760 remains a functioning estuarine wetland and, overall, it has to be acknowledged that the various efforts to prevent the environmental degradation of the reserve over the past fifty years or more have largely been successful. Obviously, for those of us who have been monitoring and generally assisting the Bush Stone-curlews on the Central Coast, our immediate concern is to have the birds return to their former habitat within the reserve. Over the years I have found that sometimes it takes a setback to shake a community into reassessing its values, not unlike ‘the recession we had to have’, and I have already written to each of our local councillors informing them of the birds’ abandonment of the site and that the situation has, for the most part, been brought about by the council’s poor decision-making in the past. For the longer term, consideration is being given to constructing a website to better connect the local community with their environment. Hopefully, by virtually transporting that environment into their homes our community, particularly the younger generation, will then better understand the richness and the diversity of the natural world that surrounds them and come to the conclusion themselves that it’s an environment definitely worth preserving.

Working to prevent the environmental degradation of Reserve R64760 has been ongoing for more than half a century. Asked if we could turn back time and choose to participate again, our answer would be yes, without a doubt, but with the benefit of hindsight our approach to addressing the environmental degradation of Reserve R64760 would obviously be a little different and better planned the second time around. However, I fear the result at this point in time would likely be the same. Disappointingly, we now live in a time and place in which too many individuals are obviously not prepared to give up any part of their ‘freedom’ or sacrifice any part of their ‘lifestyle’ for the benefit of others or for an environment to which they have little or no connection. Our personal experience of continually trying to defend just one small area of public land from environmental degradation over half a lifetime is far from the norm in our community. Hopefully, though, I have effectively presented to the NSWBA just some of the skirmishes we have experienced along the way so that other members might gain from them. With a bit of luck, by sharing our knowledge others might be even more successful in their goal to prevent the environmental degradation of their own ‘backyard’.

Alan Skinner

January, 2016.